Four Generations and Thousands of Years

Starla Thompson is a Potawatomi woman of the Otter Clan and a mother. In July 2025, I met her at the corner of Wolcott and Winnemac, at an apartment building where four generations of her family lived.

At a young age, Starla’s grandmother, Elsie Johnson, was abducted from her grandmother’s home and sent to boarding school. After surviving the horrors of boarding school, Elsie moved to Chicago, where she fell in love with and married Albert Silva. They lived throughout the Far North Side, eventually moving to the apartment building at Wolcott and Winnemac. There, they had a baby girl, Karen.

In the late 50’s, Karen contracted tuberculosis and had to be sent to a quarantine facility. Where once the US government forced Native children into boarding schools, they began to adopt them out to White families against their birth families’ wishes. Under the guise of receiving life saving medical care, Karen was stolen and illegally adopted by an abusive family in Nevada and even given a new name. This period of forced assimilation was called the Adoption Era.

But when she turned 18, Karen returned to Chicago. Heartbreakingly, despite never giving up hope of a reunion, Elsie had already passed away. But Albert had stayed at that same apartment building, which is how Karen was able to find and reconnect with him. The land called her home, and her father never stopped waiting for her.

The lands now called Ravenswood, Andersonville, Bowmansville, and all the surrounding area were home to Potawatomi villages, camps, and settlements for many thousands of years before Chicago was even founded. The land has never forgotten, and it continues to call its kin home.

After reuniting with her family and the land, Karen gave birth to Starla. Starla’s family gifted her a Potawatomi name that means The First Light That Breaks The Night Woman. Starla grew up walking to nearby Wolcott Park with Karen and visiting the American Indian Center when it was located on Wilson Avenue. The threat of family separation did not go away though, as Starla and Karen faced homelessness on their own homeland. Though like her elders, Starla always found her way home.

After returning to Wolcott and Winnemac, Starla welcomed home the next generation of the Otter Clan, her eldest son Jeremiah. She brought him home to an apartment on the first floor. Currently, there is a smaller tree in front of that unit. But when she brought Jeremiah home, there was only the larger tree in the parkway. This was the first tree his young eyes saw, from the window of his nursery. That tree is still here, standing tall and shading passersby.

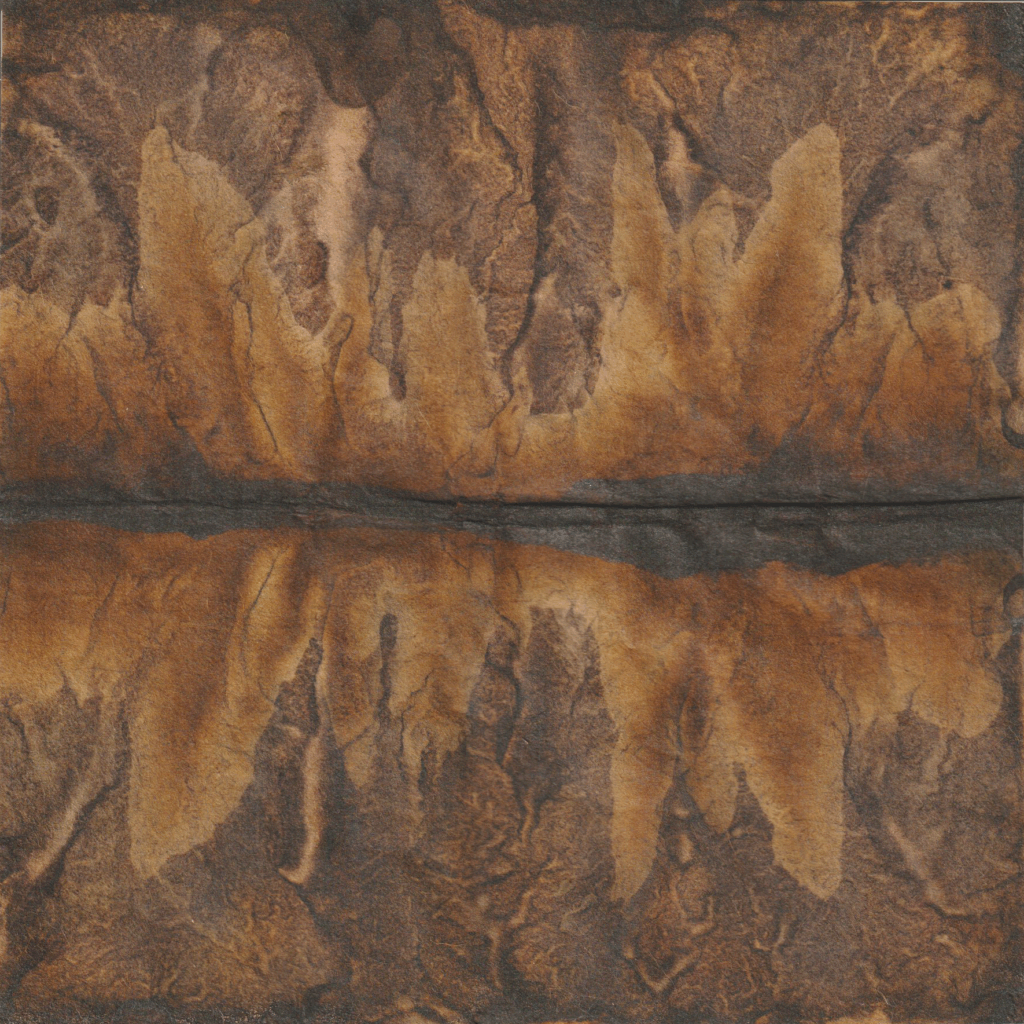

When she took me to her old home, Starla collected a piece of bark from this tree. It is this bark that we made chromatograms with.

“Native values are based on consent. We should be in a consent-based relationship with the land.”

Read an audio transcript

Native values are based on consent. And so that’s really important. And what we forget, and we should be in a consent-based relationship with the land.

Yes.

And there’s a lot of Indigenous stories that are factual about even Indian people while they were finding their ways and working their ways through their way of lives violated. There was a time when we violated our relationship with our relatives, our four-legged relatives and there’s a story about how they just got up and left us.

Sure.

As a lesson.

That’s how you learn.

That’s how you learn. And we learned very quickly, oh my goodness we were not living in reciprocity with our relative, and then so you know. And there’s ripples from that today. So that when you see an Indigenous person maybe kill a deer for their family or a buffalo and they ask that relative if they’re willing to sacrifice themself. They put down medicine in honor of that sacrifice.

Yes.

All of that reciprocity right it changes the whole way that you operate within this world.

When collecting samples, I ask everyone to think of their ancestral foraging and harvesting practices. Starla’s rich family and cultural history led her to leave an offering of medicine for the tree that has shaded four generations of her family. She said, “It’s acknowledging that what we’re going to take from this place is a living matter, and it’s a living relative. So it’s asking permission. So what I would want to do is put down some medicine, and that will change the sample right there. Because again, we’re working within our consent-based values. We’re asking permission. And also we’re leaving something as a gift.”

“I’m so grateful to be born Indigenous”

Read an audio transcript

Well I think that what this land has taught me is how to be in a relationship. So like I explained, a relationship is going to have all these dynamics and there’s gonna have a lot of history too and we don’t live in bubbles, and I’m hoping your project points to that hugely- like, it is not just us. We are not just living in this individual consciousness right.

Mm hmm.

And our actions have repercussions and you know, on an intellectual level, like you look at quantum physics right, like everything is energy.

Yes.

It can’t be destroyed so what happens? You know, it is, it changes form.

Mm hmm.

So what is our form right now? What is the form that is being imprinted on land, on others, on all living matter, right? So those are the questions that I think of. I mean I was born into a society that understands that and has, you know, and I’m so blessed. I’m so grateful to be born Indigenous, to have that foundation. It has really, land has taught me how to be in relationship. It was the first being, relative, that I was in relationship right. And like I mentioned, it existed prior to us, and so it is our first, one of our first teachers, Mother Earth, that’s why we call it Mother Earth.

And so it’s, it taught me how to love. It taught me how to be a mother because it was a mother to me. It taught me how to be a mother to my children. I have four boys. And so it taught me how to be that and do that and continues to. It evolves, right?

Winnemac Means Catfish

The word Winnemac is an Algonquin word, meaning catfish, or bullhead fish. Though Starla is of the Otter Clan, her grandmother Elsie’s sister, Josephine, married a man from the Catfish clan. Starla said, “they’re diplomats, they’re medicine people. Many of my male relatives represent that clan and our family.” It is Josephine’s son, Joseph Daniels Sr, who gifted Starla and her children their spirit names.

Algonquin is a family of languages with many distinct languages, including Potawatomi languages. And though Winnemac is often cited as a Potwatomi word, it is not the word that Starla’s family uses to mean catfish. Because of this, Starla did not know that Winnemac meant catfish until she was forced to move away from the area due to rising rents, though she comes back to visit when she can.

Hopes for the Future

Native Chicago is all around us. If only we would choose to crack open the lies colonialism has used to pave over the truth, we would see that this land and its relatives have never abandoned their sacred duties of stewardship. When asked how her hopes for her community can be reflected in the land, Starla said, “I think people long just as they do for connection, they long for the truth, they want to know the truth, they want to live in an authentic world. And so, I would like for that truth to be more inclusive and representative in this city. I grew up as a little, young girl here and never saw anything like myself represented in any way, form and fashion in this city.”

While Starla would like to see a plaque in this area, telling people about the significance of the word Winnemac, representation isn’t her only hope, “systemic change, affordable housing, those are all things that we need.” She went on to say, “I would tell my children all the time- we drive through here. I would love to move back here and they’re, ‘why can’t we,’ well, this is why. And that’s unfortunate because the land wants us back here.”

“They tried to colonize the land, just as they colonized our people, and so you see these waves of assimilation. But what they don’t understand, what a lot of people don’t understand, is that the land is a living relative. And it has the ability and power to break free from that oppression. And one way that it does that is it calls home its relatives. Like my mother, like my grandmother, like myself. And so the fact that we keep getting called back is proof of that power. The fact that our relatives chose to stay here and you know made those decisions very intentionally as a conscious, collective conscious decision that kept being reaffirmed throughout history. I mean that’s just powerful right there. And so that’s kind of what this corner means for me. It’s a representation of all that.”

Exhibition

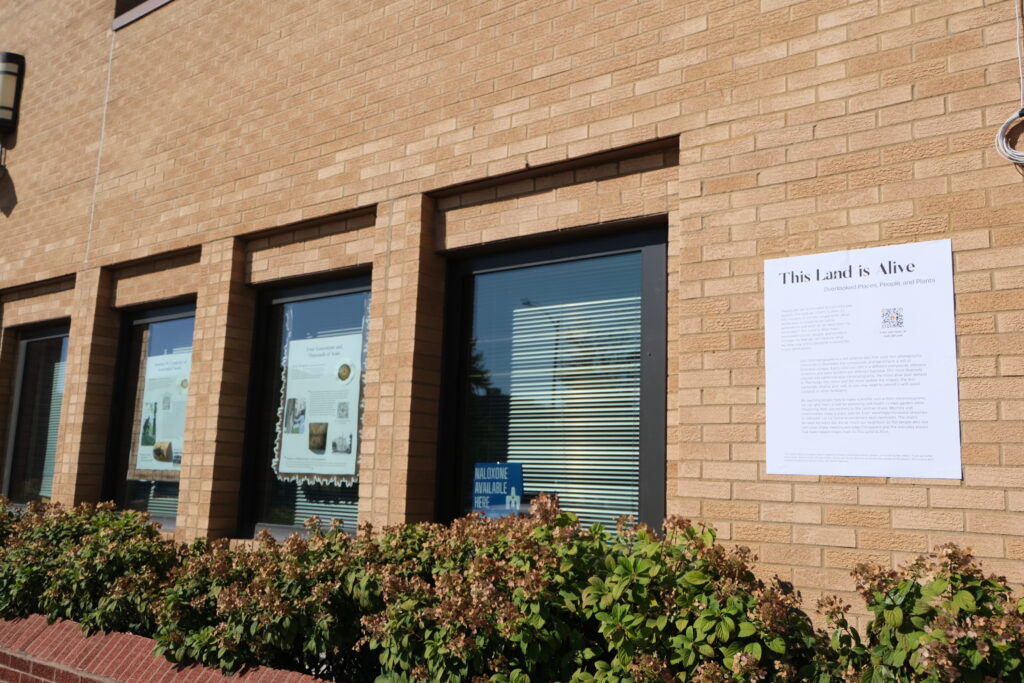

From October 5 – November 15, 2025, Starla’s story and original chromatograms are on display in the windows of the North Austin Branch of the Chicago Public Library as part of the Terrain Biennial.

Further Reading

Engage with Starla’s work at Walks With A Good Heart.

Learn more about ongoing Native history with the Indigenous Chicago project.

Chicago is teeming with life

This Land is Alive maps overlooked places, people, and plants in Chicago. Click below to meet your other neighbors.