I am so thankful to have had my show, Mari Miller: The Land Loves Us, up during both my birthday and Lunar New Year. Now that it has been de-installed, here’s a walkthrough of the exhibition for those who couldn’t make it.

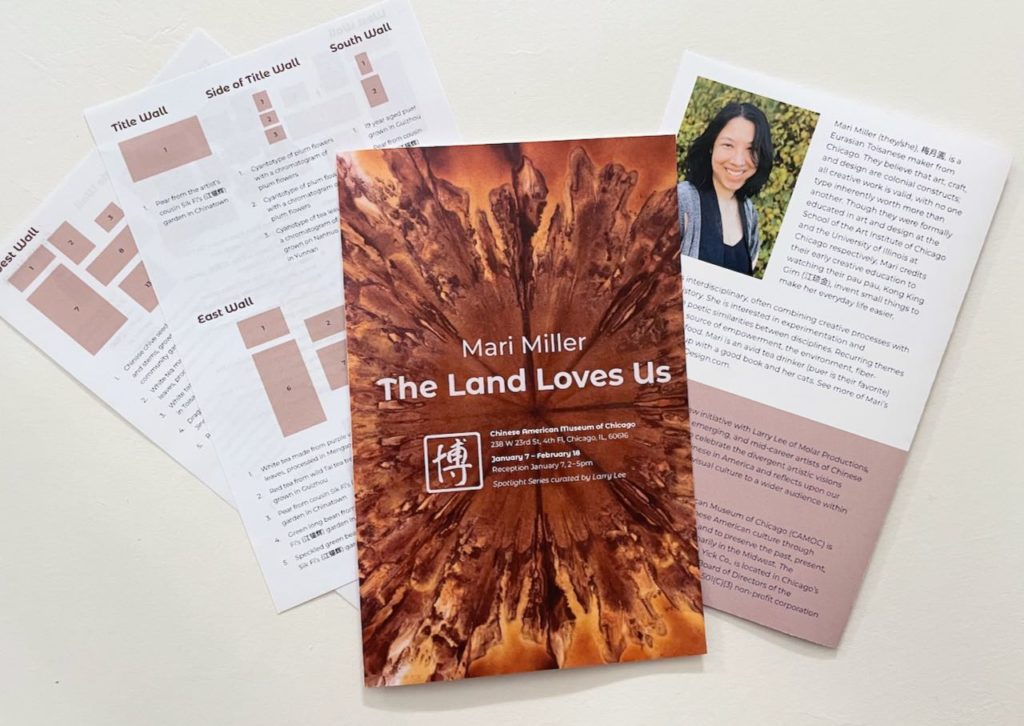

And for visitors who came on a day when my exhibition pamphlets were all taken (the museum ran out so had to re-print them), here’s the exhibition text. Note that Kinkos cut off my margins! I designed the pamphlets to have a little more breathing room than what you see in the pictures.

Click here to read the exhibition pamphlet text. Note that in many Chinese languages, instead of asking, “how are you doing,” you ask, “have you eaten yet?”

“Have you eaten yet?” Pau Pau asked, handing me a bag of baby bok choy. “Have you eaten yet?” ran through my mind when I would search Starlight Market for Pau Pau’s favorite puer. “Have you eaten yet?” the soil asks me when I harvest Chinese chives from my community garden plot.

As plants grow, they absorb nutrients from the soil. When we eat, we are eating the land and its love for us. Drinking tea with strong qi lets you feel the sun as it warmed the growing tea leaves and taste the minerals that the tree’s roots absorbed. Drinking tea is a way to connect with the land, to take in its abundance.

Chromatography is a photographic technique that allows farmers to take a type of snapshot of the components and bacteria that make up the soil they tend. I have come to see chromatograms as photos of the qi of the soil. They are a visual representation of the land and its love for us. Chromatograms cannot show us the entirety of the land’s spirit, but they reveal an aspect of the land that is usually hidden. I use chromatography to create images of the components and bacteria that make up our food, all elements that contribute to the qi of the plant, that come from the qi of the earth, that nourishes us as we grow and fight for a better future.

The cruelties and deprivation wreaked by European colonization caused many Chinese to emigrate to the very countries inflicting opium, starvation, and war upon them. Here in these foreign lands, we are subjected to endless stereotypes and violence. We are the perpetual foreigners, never welcome. Back in the motherland, we are too American, too British, too Canadian, too Western. Our people tell us that we are not Chinese But if we don’t belong in China, do we belong on this stolen land?

I believe the answer lies not in whether other people choose to accept us, but where we are able to build communities centered around love. What has become clear to me in these times of worsening climate disasters is that the land loves us. Visualizing this love is important as we experience a surge in sinophobia.

Asian diaspora obsessions with food may be reduced to memes, but in times of fear, hate, and instability, love is paramount. It is our love of the land and the food that grows from it that will lead us to fight the companies and governments causing the worst climate abuses. It is the love and examples of our ancestors that will give us the strength to rebel against fascism- afterall, the majority of the Chinese diaspora comes from a region of China that has been the site of numerous rebellions. And it is love for our neighbors and family that will push us to build safer, supportive communities alongside our Black and Brown kin.

During the opening, I gave a short artist’s talk with a Q&A. Watch this video to hear me speak about the soil chromatography process.

One of my favorite aspects of the show was seeing how the banners helped change the atmosphere of the space. I’ll be writing a making-of post for them.

night after a day of brewing, grown on Nannuo Mountain in Yunnan

Another favorite aspect was seeing how my prints changed over the +1 month the show was up. Soil chromatography is a photographic process because it involves silver nitrate. The prints can take a week to fully develop under the summer sun. In the winter, they can take about a month to develop. It’s always a fun surprise to see what colors and details will emerge over time.

In the week leading up to the show, while I had plenty of prints to fill the gallery (and another one or two), I realized I didn’t have good prints of some of my favorite teas. I love dragonballs, which can refer to tea that’s compressed into a sphere, but can also refer to tea stuffed into tiny oranges. Though any orange could be used, authentic oranges are grown in Xinhui, Guangdong, the same region (though not the town) my family is from. I made chromatograms from this type of tea early on in my explorations, but realized I hadn’t made any once I had refined my techniques. So I created some last minute prints of dragonballs and got to watch them develop as the show went on. I love how they started out very flat and graphic with high contrast, then developed new colors and details over time. The photos below are of the same print made from a dragonball composed of white tea from Jinggu and an orange from Xinhui.

Watching prints develop is like watching the learning process. You start out with learning the broad strokes of a process or concept. Over time, as you sit with and contemplate the work of learning, your understanding changes. You learn to see nuance as your knowledge (both intellectual and somatic) deepens.

I am extremely proud of my first museum show, which was also my first solo show. Thank you again to Larry Lee for curating and the Chinese American Museum of Chicago for hosting my work.

Leave a Reply